Decentralized organizations 4/x - decision making

Next: Example of Decentralised Organisation

In the previous post we introduced the high-level components of a DAO and how to get one started. Now it’s time to look at various ways of making decisions.

At the heart of any organisation is the shared purse – the funds the organisation has at its disposal. Decision making model defines how decision about its usage are done and who can participate. In many ways it is the core internal logic of a DAO.

Let’s jump straight in to different ways decisions are being made and can be made.

Traditional – linear, delegation, managerial, unanimous

Voting is the traditional way of approving proposals. In private companies the number of votes at shareholders’ meeting is based on number of shares i.e., money you have invested. Inside the company decisions are made by responsible managers following companywide policies (like approval levels, domain they are responsible for). For bigger decisions like introduction of new portfolio products or product lines, there are boards with higher-level managers as decision makers. They tend to favour unanimous decisions. As downside any single manager can prevent or at least delay decisions they do not like by besserwissering over some detail. This mechanism is sometimes called a vetocracy.

On national side delegated models are used where each citizen has one vote and a set number of decision makers are elected for each election period. Different selection models like first-past-the-post or relative systems like d’Hondt are used. Public organisations in turn function inside with similar hierarchies like private enterprises with responsible managers or boards making decisions from proposals. The major difference is that they are usually monopolies by law and do not face pressures of innovative competitors.

In small associations and micro-enterprises preference can be for unanimous decisions.

General problems with decision making

Voting is however not a method for decision making but for dispute resolution. In representational democracy the dispute is over who gets to make the decisions, in companies and web3 projects the dispute is over whether a proposal is funded or not.

All the essential choices are made before the vote. Decision makers/voters never see what other options are possible or if there would be a larger problem in society/company/project worth solving (so called opportunity cost for not doing something better).

Neither can voting be used to make decisions about the myriad of small details in the proposal. Inside companies the essential technology selections affecting company future are done long before managers see them when a group of people pick up a set of vendors or open-source tools for evaluation and leave others out.

Nor do voters usually do rigorous background test to verify that the presented data is valid and without error. The world’s most common decision-making tool is a spreadsheet with simple mathematical errors buried deep inside. Spreadsheets are used to build simple assumptions like market grows every year with the same amount and prices decrease linearly. Seldom does the future obey such commands.

The fact that people are busy and have other things on their mind is just a fact of life. Some mitigations can be achieved for example by asking for some background data and alternatives to be considered and logic for the recommendation or simulations about proposed change. In web3 the practice is to publish the proposals and have the community discuss about them until the proposal makers feel it is mature enough for vote.

Another option is to improve the general understanding of the business context where the project is. This can mean for example building real-time displays of the business activities and making them generally available to anyone. For better reach the organisation needs a person responsible for communications. Someone posting about changes and latest developments on various channels, issuing a small email newsblurb, making interview videos with domain experts etc.

But the fundamental issues remain and it is good to just be aware of it.

Granular Delegation

One proposal to improve current national decision making is to make delegation granular.

No one is expert in all areas; however, we select our representatives for all topics in elections. In granular model on national level, I could vote for a different person to represent for me in defence issues and another on health and let a third person handle the rest.

Claw-back rule says that if I am not happy how my delegate is going to vote or if I view some topic very strongly, I could take back my vote on that specific issue and vote myself – i.e., lock my view on it. This model is called liquid democracy.

This sounds good but it may prevent looking at the big picture as we can end in a state where all representatives just look to maximise common spending on their sector and do not care how the overall economy or society develops.

This could be averted if decision making is split into two parts. First the general division in spending is agreed between sectors like safety, health, education etc. and after that delegates make decisions within their area.

Cross-cutting concerns are the loser in this approach, but they are also in the current model as in practice proposals for decision making bodies (parliament) are made by ministers and each ministers tends to focus on their own silo with ministerial staff sharing their bias.

Quadratic Voting

In quadratic voting participants can express the degree to which they support a proposal. Instead of casting all votes for one of the proposals, it is possible to split ones voting power to two or more parts and use some number of own votes for each of those. The amount of votes for each indicates strength of support. Every participant has some budget within they vote. Typically, the number of tokens is used.

But the votes are not counted linearly but a square root is used. This means that someone who has invested a lot and has a large number of tokens cannot simply overpower many other participants that have smaller number of tokens.

So, in counting the votes the scheme would be as an example like this:

For more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quadratic_voting

Conviction Voting

In conviction voting the vote for a choice is continuous. You do not vote once but express your liking for an idea and the longer you keep my choice for it, the stronger the vote becomes.

The same is true for reverse. If you remove your stake for an idea, the stake starts slowly moving from old idea to new idea.

As an analogy, the voting works like filling in a large bottle through a narrow hose.

This mechanism prevents last minute fake news trumpeted widely from affecting major elections. It makes also difficult for wealthy or powerful to buy or use fear of violence to swing votes. People could stake their vote after bribed but after the payment they can immediately change their vote nullifying the effect. The affluent need to constantly keep paying for the vote (or to constantly maintain the fear). Both are expensive mechanisms.

Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are not really a decision model but a way of gaining an independent opinion of some question. They are based on the concept of wisdom of the crowds. Two opposite questions are posed. People can stake in either claim and when the matter is resolved, the winning side shares the whole pot.

Since there is real money involved (skin in the game) and an option to gain easy money, people will stake based on their best understanding or asking from real experts. The results are expected to be close to an independent experts’ opinion.

Prediction markets could be used for example to predict economic development, future stock prices or to signal citizens opinion. For the last part a typical claims could be e.g. “Now that construction on main road A is finished, city will close it again within next 12 months for another uncoordinated road work” and another claiming that this time unconventionally there was some co-operation between city departments. The results would tell the city the independent opinion of residents on their ability to plan ahead and make the public opinion visible in a way that the city cannot deny.

Futarchy

Futarchy is a proposed by economist Robert Hanson and is a way to make public decisions where elected officials propose policies and prediction markets are used to determine which of them would be most effective.

However, prediction markets are pay-to-play environments and with large investment one could de facto force the markets to tilt in favour of one or the other side even when this is not the view of the majority. It’s different to signal to municipality or government that they should get their act together compared to decisions where millions are allocated and the beneficiaries could at the same time participate in prediction markets rooting for themselves.

This can be damped with the square root method, where payment to influence decisions grows exponentially.

Random Decision

Last method of making decisions is to let random number generator make them. This is a little bit counterintuitive, but perhaps three examples below help to understand.

Most development aid stays in capital or other big cities where the employees of recipient organisations tend to live. A low overhead alternative would be to hold a continuous raffle and just give aid directly to the poorest in rural areas or to their organisations. Divide aid amount to smaller sums and raffle it away in small parts. Then follow up and see how they invest it and what impact this model has on development.

Since money could be won any day just by living in such an area, this would have a tendency to slow down moving from countryside to big cities. Large migration of people from the countryside to bigger cities after better earning potential poses problems to many countries. Arrivals tend to pack into informal settlements where living conditions are poor as as cities have difficulties building new infrastructure fast enough and they often lack funds to access housing.

Another proposed idea is on election. The number of sleeping voters tends to grow from election to election. This can be viewed as an opinion from voters’ side they could not find anyone they would like to represent themselves. Since we do not know what their preference are, it is a little inconsistent to allocate all power to those they did not vote for (de facto endorsing rejected opinion). We could in turn use random decision making and arbitrarily nominate the proportionate number of seats to people who are eligible to vote. If someone does not want to take up the set in the parliament or municipal council that they won in the raffle, that seat would be empty (a double-no; choose not to vote, choose not to take up a seat).

This means that number of decision makers tends to fluctuate between elections somewhat and that the political parties get the representation in decision making bodies that reflects their true support.

In similar manner research grants tend to go to people who work for well-known universities or research institutes and follow mainstream ideas in each field. As an alternative grants could be given in random manner for researchers for a short while and if their direction seems to produce results, continue funding.

Curation Markets and Bonding Curves

Funding a project itself is a decision to support a particular project. If these tokens purchased are governance tokens, then they naturally give decision power down the line in detailed issues.

The simplest way to fund a project is to purchase tokens from the team directly as token warrants etc. but curation markets are an interesting variant. In it tokens are purchased from a smart contract, details below.

Curation markets are an idea invented by Simon de la Rouviere in 2015 and can be set up in many ways. It can be used to order a list in the order of importance, to validate some entry into the list as we saw in IP-NFT example or a way of funding some project.

The scheme is as follows:

At any time, people can buy tokens associated with the project. The price is set up by a smart contract and it is set to increase the more tokens have been sold. I.e. as more people get interested and buy into the project. The fact that price goes up with interest creates incentive to be the first to find meaningful projects.

The funds are kept at a shared purse. People can also leave at any time and sell their tokens with a price set by a smart contract. This means that the token is always liquid – you can buy and sell at any time.

The smart contract acts as an automated market maker.

(A market maker in normal markets is a party that at the beginning of the trading day steps in and makes the first buy or sell offer when no one else wants. They basically say: “I think the market price now for this asset is X” based on their experience. Seeing that trade is going on, others join and the trading gets going. Typically, some financial institute acts as the market maker. Here an automated smart contract does the same.)

The sell price does not need to be the same as the purchase price leaving a gap. This is useful when there is a beneficiary – i.e., this way projects can get funding. The market is used for example to fund design and development of some physical product or software.

The bonding curve can be any shape the team decides – exponential like above or linear, S-shaped or follow any other shape. The programmatic nature of tokens allows adding all kinds of additional rules – like locking tokens up for a set period so that folks who purchase tokens cannot immediately sell them back or vesting schedule so that the project team cannot immediately access the newly granted tokens.

The fact that the sell price lags behind the buy price and optional locking periods discourages fast pump-and-dump schemes. Also, if the investors are not happy what the team does, they can all decide to sell their tokens effectively drying the team out of funding.

Curation markets can also be used only as a signal for the importance of something. The first use for curation markets was to allow folks to indicate what entry on a register should go to the top – say define priority order of news or popularity inside a category of art. In that case the buy and sell curves will be identical and the only cost for the purchaser is the opportunity cost (opportunity cost = what other cool or profitable thing you could have done with the money) while the money stays around locked in the contract. These types of registries where tokens are used to vote which entry goes to top are called Token Curated Registries (TCRs). Curation markets are good in areas where subjective information needs to be curated. Different people have different opinions what is the best restaurant or most interesting point of interest.

In IP-NFT case (previous post) we saw how TCRs could be used to signal the trustworthiness of a potential buyer.

Attacks on Governance

Even with all these new ideas in governance, it’s not all sunshine and rainbows.

There are many ways to attack governance processes. The most obvious is called Sybil attack where some party with lots of resources (individual, group of coordinated people or nation state) purchase a large amount of governance tokens. They create one or more synthetic users on the platform or bribe real people to make proposals on behalf of them and then en masse vote for it. As a low-cost option dictatorial states can order their constituents to vote in particular way or hand over their wallet keys.

Voters can be bribed to vote for a particular vote in indirect ways as well. For example, by creating a decentralised finance (DeFi) service that pays you dividends if you “stake” your governance tokens there. This happens so that you send your tokens to a smart contract that gives you back another token as “receipt”. You can at any time use your “receipt” token to get your original ones back. On top the service pays a dividend. This service might be a front for a team that wants to steer a project in a direction that benefits them directly or they could just auction the voting power to the highest bidder. The negative side of this is that anyone holding the original tokens also has vested interest in them holding their value and the actions of malicious actors are likely to destroy it.

Attacks can also be indirect as follows: You use some DeFi service to stake some value there and get “receipt” token back. Then you use your “receipt” token as collateral to loan some third tokens from a DeFi loaning service. You now have governance tokens in a third service with no direct financial linkage to you. You use these tokens to vote in a way to favour you financially or auction away the voting power.

Some work ahead in the web3 world to figure these out. Some projects are using as partial solution timelock techniques that require users to lock their coins and make them immovable for lock period in order to vote. These prevent fast buy→vote→sell attacks.

What the web3 community has to counter for now is the culture of openly sharing experiences and ideas, ability to respond rapidly with global talent pool and perhaps ultimately forking (starting over) successfully attacked projects (may work or not depending on project type).

But it is going to be a bumpy ride.

For more see: https://vitalik.ca/general/2021/08/16/voting3.html

Gardens

There is a dilemma at the heart of governance. Projects need to attract capital to get the initial development funded so something useful comes out. The investors want to have a say what is done with it and governance tokens provide that decision power. They have skin-in-the-game and this is good as it ensures avoiding undue risks and costs.

At the same time this easily leads to situation where decision making is centralised and other participants get poorly represented leading to a situation where there is no way to hold central power holders accountable to the greater community.

Gardens is one recent proposal to address this. It is based on three parts already discussed in this chapter:

Conviction voting. Good part of conviction voting is that no large token holder can prevent your idea as there is no downvoting. Different ideas for features can co-exists at the same time. This could lead to constant streams of divergence and convergence (or it can lead to a mess of conflicting implementation leading to a fork in project).

Written constitution containing values rules and customs that everyone joining agrees to adhere to. It is a plain language document

Decentralised court system used for dispute resolution. Court uses the constitution as a basis for making judgements. (see below).

The Full Ensemble - all bits on stage

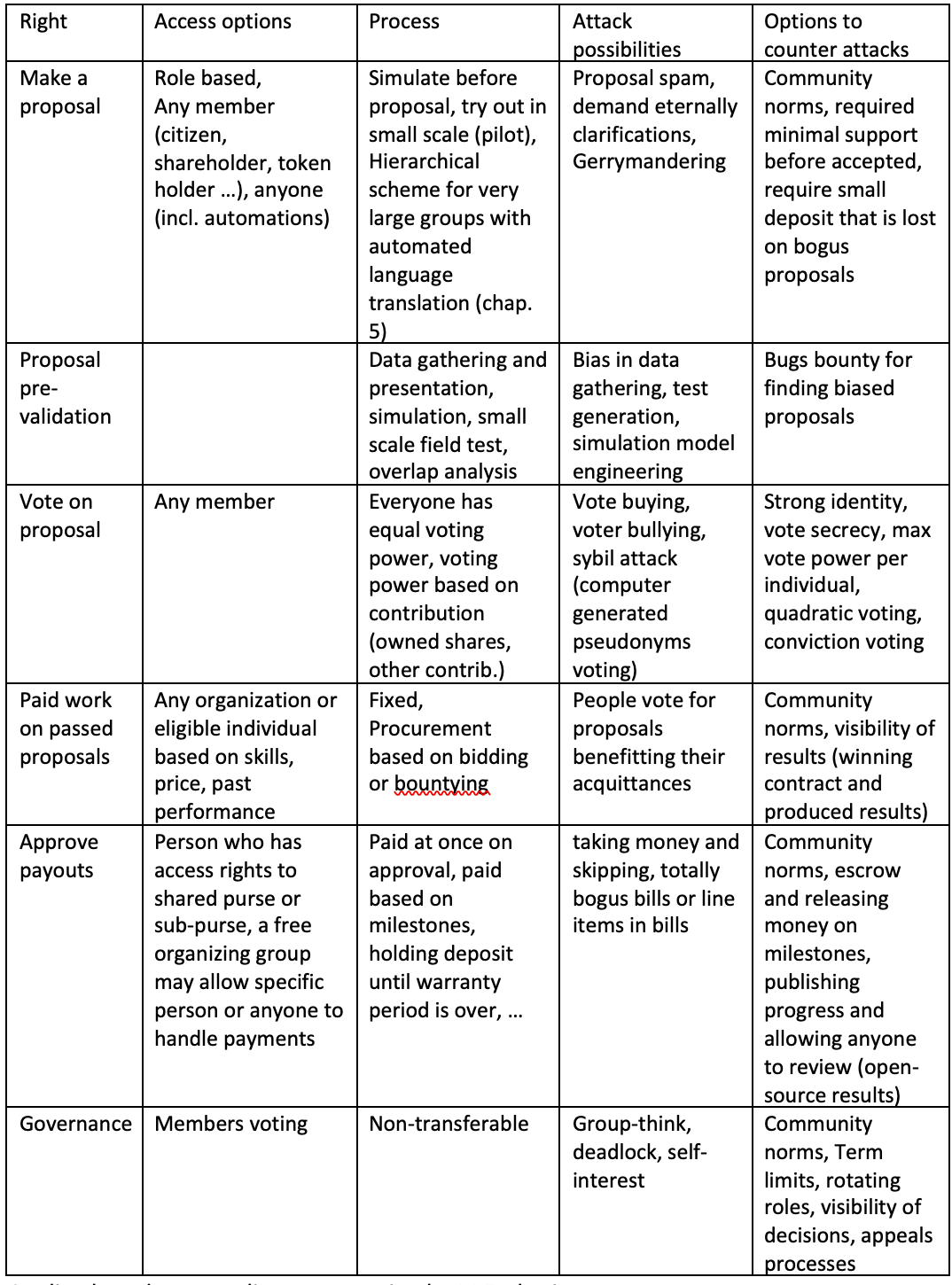

Any decision-making system has a number of parameters that define how it works. Things like who has right to put forward ideas for the vote, how voting proceeds etc. All phases have potential to be gamed for personal gain and mitigation methods need to be developed. These can be visualised in the table below:

Credits: based on an online presentation by M.Zarkavi.

The programatic nature of tokens allows to experimenting to find new models of decision making and to iteratively find out if different modes of governance could make sense in different could cities follow different models as long as the service levels for residents remain (but could increase with same spending)?

Decentralised Jurisdiction

It is impossible to account for every possible circumstance in the code of an automated organisation. Code can be written to deal with most common exceptions but it is normal in disputes that the underlying things are subjective and up to interpretation. Different parties see the world in different ways.

The problem can of course be solved by indicating in the bylaws of the organisation where (in what country and under what legislation) disputes will be handled. In global projects everyone is in a minority regarding living place, selecting one jurisdiction would mean that most participants do not know what this means in practical terms nor is it reasonable to expect that most would enjoy finding out. This can prevent large-scale global co-operation.

Decentralised jurisdiction to the rescue.

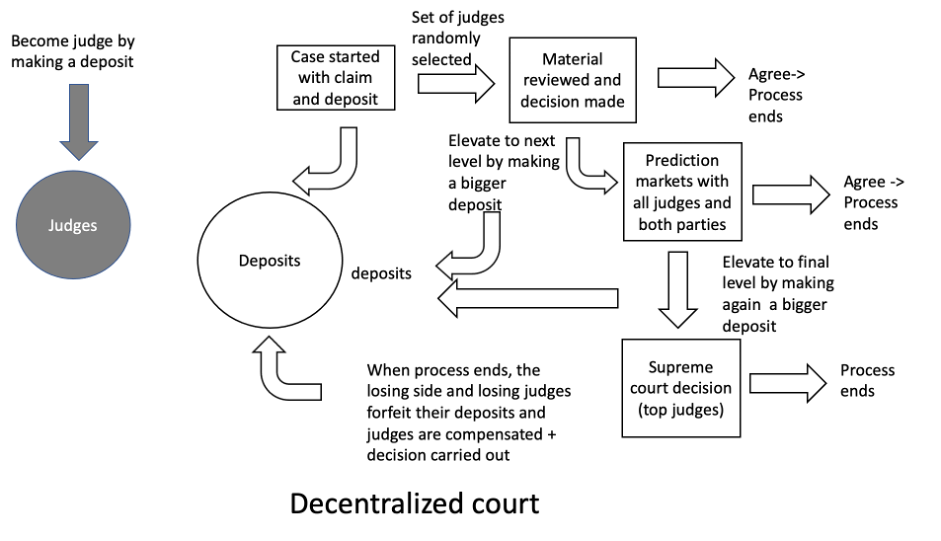

Let’s go over one example. It starts with rule that anyone can nominate themselves as a judge by placing a deposit (money). The idea is that if they make bad decisions that ultimately get overruled in appeals process, they lose the deposit.

A party that has been wronged, can start a process by stating their case and making a deposit. Defendant responds with their material. A set of judges for resolution on first level are randomly selected from the volunteer judges (that have skin-in-the-game via their deposits). They view material from both sides and make a resolution with explanations. If both parties are fine and dandy, the process ends.

If either party is not satisfied, they can make an appeal to next level by making a new larger deposit. On the second level, the decision is made by prediction markets where the market participants are all of the judges of the system.

As described earlier prediction markets work so that participants stake in money on the resolution they deem as correct. The winning side will collect all the money. Prediction markets work, because people that strongly think that they are legally on the right side are willing to deposit more money than a side that just wants to make easy money without effort and knows inside to be wrong (or did not bother to check anything). That’s the theory anyway. They can also misfire when people start siding with the opinion that seems to be winning, but here the further levels of appeal pose risk of losing own deposit if one goes with an incorrect view.

If some party is not happy at this level, they can elevate the case to Supreme Decentralised Court. This consists of a set of top judges – persons who have gathered the most winning rulings. The decision of the supreme court is final and ends the process of decentralised court.

When a decision that stands is made (i.e., final decision or a decision that is not elevated), the losing sides forfeit made deposits. Also judges that have supported losing side will be financially penalised.

If some party things still they’ve been wronged, they could naturally start a process through some national court system, but it is too early to know how that would work. The DAO itself may be legally represented as a non-profit organisation or association and does not have much funds. The Treasury of the DAO is collectively controlled by all the governance token holders and only their will can cause any transfer of money from it. Some of the participants are likely to be pseudonyms as well.

And at the end of the day everything on these projects is based on social contract so any shady rulings manipulated through a corrupt national court system would cause participants to deplete the original project of its resources and continue with a fresh one.

To prevent a well-funded body to overrun the system with bots, know-your-customer type of global identity is preferable or more advanced cryptographic systems that ensure uniqueness of participants without revealing their identities (sounds impossible but the crypto-world is working on such wonders).

How this pans out remains to be seen. Decentralised courts could be made out of participants of a large projects internally or be an external services that projects agree to use for disputes. Gaming attempts are likely to be seen. Even when global ids are used to validate that all participants are real people, a large enough autocratic state can overrun the system by forcing its residents to act in preferred way. Hence certain nations might be needed to be restricted from participation although this would be against the ethos of the current web3 community.

You can read more from one project (Aragon) developing this idea further from their blog.

https://blog.aragon.org/aragon-network-jurisdiction-part-1-decentralized-court-c8ab2a675e82/