Decision making in a Decentralised World

Next: Solving Complex Problems

The idea behind decentralisation is to distribute the decision power to the community that participates to the project in one or the other form – software developers, trainers, documentation creations, machine learning model makers, graphic artists, people helping others to join by answering questions on forums, speaking on events, making video materials, creating helpful suggestions, linking project with other projects for synergy etc.

But not everything is as it looks on the surface in the decentrala-la-land.

When we look at existing successful web3 projects they almost inevitably seem to have either an open or hidden centralised component in decision making. This often is the initial project team that made the first implementation and that has a sizeable portion of tokens at their ownership or control via a fund of some kind. They have deep understanding of the original vision, technical know-how of the implementation and prominent position in the community having started it. Challenging them to a new direction is not easy.

Sometime the token ownership is completely dominated by venture capitalists that funded the development and the initial implementation team. There is often a promise of handling over control to the community at a “later time”.

Other cases there is one leading figure who blogs about future development ideas and the community tends to more or less follow those guidelines.

And in cases where there is no clear owner, the communities seem unable to make any decisions. Even the most minute changes result in heated months long debates that from the outside seem more related to who gets to decide rather than what is decided.

Smart contracts seem to work well in executing policies once they have been agreed upon but the future direction of projects seems to favour expertise that is not widely disseminated.

This is quite natural. The modern world contains so many complex physical and digital services that to assume that everyone is deeply aware of all nooks and crannies of everything and has a feeling or wants to read and analyse all simulation results of every change, is simply not at all realistic.

Some format of delegation in decision making seems inevitable and this delegation leads to centralisation.

Let’s consider a few options to balance things out.

Sogur way

Sogur project introduced a model where everyone participating belongs to Assembly. It’s up to personal choice whether one wants to participate self and cast votes or appoint a delegate. The assembly appoints (hires) the people who run day to day operations and make daily decisions

Sogur provided only one service (global money), so in a more complex case like decentralised community adaptations might be needed. For example for people to appoint different delegates to separate domains (like energy, defence, transport) as it is unlikely one delegate is a jack of all trades.

Sogur also had other “departments” with nominated people like one for initiating smart contract changes and looking at long term strategy and one for dispute resolution. In essence there are different expert entities allowing specialisation into a particular topic. You can see the full model here

Sogur and dynamic allocation of voting power

In national elections voting is identity based – one vote for each person - whereas in private corporations’ power is related to number of shares in the company.

Let’s call the one person one vote principle as participant-based and how much you have invested as stake-based approach. Both have their advantages and disadvantages.

The more a person has invested in a project, the bigger skin in the game they have in it. It is fair that they should have a bigger share of the control in the decisions. These pay-to-play mechanisms have risks as someone buying a lot of voting power to influence a decision where they have some external interest (such as forcing the project to do business with their other assets).

Participant based network have risks where the majority favours themselves or discriminates the minority. A typical example would be welfare state where most people are receiving more than they contribute. There is tendency to every year want more, rising taxes. There is less incentive to put a lot of effort into building new companies or helpful innovations as the payback gets smaller and smaller. Fewer and fewer people do it. First the growth stalls, tax revenue is not enough, state starts to finance itself by debt or printing money leading to inflation and growing costs for the debt etc.

Both have merit but alone cannot be the full answer. A mix of both could serve better, but what would be the right balance?

Let’s consider both ends of the spectrum. If wealth is fairly evenly distributed, stake-based voting risks are smaller (no one has large wealth for buying influence). Move voting towards stake-based (token) voting makes sense as it represents the commitment (skin-in-the-game) of participants. If on the other hand wealth is unevenly distributed, wealthy individuals can purchase majorities and taint results to their favor. Participants-based makes sense here.

It seems natural that the voting power should adapt dynamically based on the distribution of wealth. And there is already a good metric for distributions – the Gini-coefficient.

Sogur adapted this approach and used the following formula:

Vp= (value in proportion to population) = 1/number of participants

Vs= (value in proportion to total value of assets in system) = (the stake of a given participant/) total value in the system

G=represents concentration in a population. Value is between 0 and 1. The bigger the concentration, the closer it is to 1.

Then personal voting power of a given individual is = G*Vp + (1-G)*VsS

Agent-principal problem

The agent-principal problem is still present. In a project there are too many low-level decisions to be made so that token holders would realistically have the time or interest to spend the effort for deep understanding, hence some format of delegation is needed. In communities with very low voter participation there is risk of capture by people with funds or small activist groups. In Sogur token holders elect a committee to do day-to-day operations. The interests of the agent are not always lined with the delegators and the agent may act in a way that benefits the agent and harms the principal. And these people are in superior position to make proposals/decisions that over time move more power / favor them.

Below are some approached to address this (not used in Sogur to my knowledge)

Disputable voting. Participants give voting rights to delegates. There are two voting rounds. First delegates vote and delegators (ultimate voting right holders) are informed how their delegate voted. If participants are not happy with it, they can take their vote back and cast it themselves. Final round aggregates results. Delegation could be just for some domain and be time limited (term-limits).

Smart voting/statement voting. Token are programmable so more specific rules can be added to delegation like “I delegate X but my delegation cannot be transferred further”.

Various other approaches

Vote buying is one of pitfalls, and here is one approach to dampen it:

Conviction voting is a system where full voting power is not immediately transferred but voting “power” moves continuously over time to the chosen alternative. It’s compared to opening a faucet where water starts flowing to a particular vessel slowly. Voter may at any time change the vote and then the first vessel starts slowly draining and another filling. This makes for example voter buying hard as the payer needs to constantly pay the voters, otherwise they will revert their decision.

Levelling the playing field for token voting:

Quadratic voting is a way to modify token voting that dampens the power of big token holders. In it the square root of token amount is used as voting power. I.e. 1 token is counted as 1 but 81 as 9 and 10 000 as 100.

Let’s see one more approach voting

A16Zcrypto posts

A16zcrypto has published a two-part blog series on an approach to solve the governance of DAOs. (part1, part2). I’ll try to summarize.

Machiavellian view is that democracy as self-government is a myth as it makes no sense with individuals with each having low-voting power to dedicate their time to study and form well balanced views on all tradeoffs. There are too many issues and any of them is hard work (or should be…). As the organization grows, it’s natural to divide work so that people who have the skills and interest work with their own topics. This includes the skill of managing and organizing activities. Hierarchies emerge with a class of people on top.

Constant opposition is not enough as elites will always try to game the system in order to preserve their position and prevent churn. The churn among leadership must be forced. Any static leadership will ultimately fail. One approach to limit this risk are term limits. A leader has maximum time they can act in a specific position.

The article makes a few recommendations

Embrace governance minimization

Establish a balanced leadership class that is subject to perpetual opposition

Provide a pathway for the continual upheaval of the leadership class

Increase the overall accountability of the leadership class

Governance minimization is based on a notion that every decision the project makes is an a potential attack vector that elites can use to game the system. The less there is such attack surface, the more robust the system is. At least three types of decisions need to be made

Parameters of the system. Most projects have some parameters like fee-percentages, inflation rates that control its behavior

Treasury decisions. Projects collect fees or gain income through other means like token issuance that are stored in the Treasury. What type of developments are done with these funds is something the members must make.

Protocol maintenance and upgrades. Changes to the system itself.

Balanced leadership class is achieved when there is perpetual opposition towards the current ruling elite. The article recommends a bi-cameral (tow-part) governance layer

First to represent the stakeholders – stakeholder council. These are parties that are deeply integrated to the system but do not hold any tokens. Technically this can happen so that each unique participating person receives a non-transferrable NFT.

There naturally needs to be a system based on which NFTs are assigned.

Any stakeholder council is subject to the risk of hostile takeover if the same party directly or indirectly controls multiple clients.

One way to address, would be to rely on national digital identities (technically signing keys that passport authorities assign to you).

A different example is Gitcoin that a system where participants collect “stamps” from different authenticators around web2 and web3, such as ENS domain names, BrightID, Proof of Humanity, Google or Discord. Based on collected authentications from various parties, various contributions and achievements, a score can be calculated. Based on the score different criteria can be set up for access rights, like a minimum score to access a voting. Same score or NFT assigned based on it can be used to grant access to making proposals or attending planning online events etc.

Second council – the delegate council – consists of token holders. People who have invested their own money or work directly into the project. As voter participation is normally low (no time to invest into deeply following the myriad of different projects and low own voting power), best approach is to delegate vote to a representative.

Together, the stakeholder council and the delegate council would have the power to approve proposals brought before the DAO. Different approaches are possible on who has right to make proposals and to veto. This effectively requires both parts to negotiate on proposals.

This concept is effectively relying on self-interested factions.

Continual upheaval can be achieved for example with term limits for stakeholders on the stakeholder council. The criteria for membership in council periodically re-measured and people having been too long members no longer considered.

Second option is to enable token holders to remove and replace delegates at will combined with terms otherwise ending on a periodic basis. Then voters would need to vote again for their delegate.

Or empowering token holders to directly elect some of the stakeholders on the stakeholder council.

Leaders need to be accountable for their actions.

Re-delegation at regular intervals means that leaders must compete for their seat regularly. They have the best insight if some mismanagement is happening and it is in their interest to expose competitors of any wrongdoings.

Voters naturally will withhold their support from any members of the elites they see is not serving their interests.

Robustness of the ecosystem is one more key factor in systems that are based on people joining on free will (opt-in). Let’s consider our case decentralized case where blueprints for essentially everything are in large repositories in open-source format (free to use). Discovery services (search or autonomous agents) are used to find the right results for each user based on their preferences and needs. Finally, the results (products, medicine, food, energy) can be self-made or made by someone nearby and purchased with value tokens of some kinds.

Robustness here means that there can be multiple competing repository systems for the same vertical. Each repository can run on one or more blockchains (or other execution environments). Creators are free to publish their output on any of them and the repositories are free to switch underlying blockchains (execution environments).

There will also be multiple competing discovery services and users are free to use the one that serves them the best and switch if not happy with current one.

Customer are also able to purchase the end result from any of the competing manufacturing facilities if they do not want to make the thing themselves.

If the leadership of any of these competing services on any layer mismanages, users will simply switch.

On project level a good approach to gain robustness, is to kick start multiple independent teams that contribute to the project. This widens the base from which people grow to become further leaders of the project. A common approach is to have a grant program where different teams are given money to do some meaningful work for the project. This could be in the area of marketing, education, development or so on. In effect grant programs are a way to pay for new teams to onboard and start competing with the original team.

The Important Stuff Happens Before the Vote

Anyone who has ever worked in a large company or organisation knows that the actual decision is made before the decision is made.

Out of the infinite number of alternatives that a given amount of money could be used, two or three alternatives are presented. And smart proposal makers know how to slightly taint the unwanted options to make them look unrealistic, expensive and risky. Effectively making a multiple-choice list with one right selection and a couple of dead ones.

We covered mitigation methods much earlier in discussion about public sector evolution in the future. Here is a short summery of what can be done:

The first one is naturally to open up the proposal making process. In the public sector posts this was called the “Open Ministry/Open Municipality”. The “Citizens’ Automation Budget” is a similar concept where people can use part of their own tax money to fund important developments (for them) when they group investments together. Very similar concept is in crypto-world where people lock tokens into a project and then allocate some of them as grants to proposals that they support.

But quite much more can be done as well in the process.

The better informed the decision makers are, the better decisions are likely to happen. Below some approaches to this:

Educating delegates on the domain. There may even requirement that a delegate has completed certain trainings before being eligible. Drawback is that such systems can be weaponized to rule people out.

Seeing if the rule is already in place (on society level, crowdsourced legislation services receive all the time proposals for things that are actually already law of the land), analysis if there are overlaps with other rules and suggesting prioritization or resolution mechanisms.

Simulation of effects at least to some degree and publishing models so others can “debug” them. Downside of this is that it can be weaponized to cause complete halt as all models are abstractions and thus imperfect. Token model simulators like cadCad and Machinations are examples of simulation tools. The drawback of simulations is that they are only as good as the model and the simulation models are also software that may contain bugs. Result may look reasonable but still turn out later to have been quite incorrect.

Field trials to see results. Web3 test networks can be seen as one way to do field trials for digital products.

Prediction markets can bring understanding to decision makers what the general public really thinks of the proposal.

After the decision it is important to follow results

As part of a decision, metrics are defined and later monitored and published

When things go pear shaped, a post mortem analysis is performed so that the decision-making process can be improved to prevent things in the future (or it is decided that a truly unexpected thing happened). Drawback of such systems is that they tend to make processes longer and more complex finally halting it as people just focus on fulfilling requirements and the actual targets gets lost.

So called Arrow’s theorem says that there is no perfect solution to governance and the party that forms the questions and outlines how the problem should be solved, direct the decision to a particular direction.

In more detail it says that there is no electoral system based on members ranking options that satisfies three fairness criteria:

If every voter prefers alternative X over Y, the group prefers X over Y

If preference between X and Y remain unchanged (but other preferences change), the preference order between X and Y remains unchanged

There is no dictator, no single one having power to choose the outcome

Fundamentally participants have different interest and worldviews and it is sometimes impossible to find alternatives that satisfy all. There may not be a correct solution to a problem that everyone agrees.

Better information helps to build shared understanding and people to agree on a wider set of things that are true, but issues will remain where disagreement exists and interest differ.

There are a few ways to address this. In next post, we’ll take a peek at that. But before that…

Governing Forces and Decision Making

The structure of stakeholders is something that has big impact on how well decision making is going to work. We discussed this in the post of governing forces.

In small local communities, everyone knows everyone and can just gather together to make decisions, in global communities people’s identities may not be known and they may even understand language in different ways due to cultural backgrounds.

Let’s look a little bit more in detail.

Just to re-iterate once more, we have a setup where local communities are self-sufficient to a large degree. They co-operate regionally with each other. Global co-operation happens via smart contract and token incentive-based projects that share digital assets though repositories (similar than what GitHub today is for code).

We have two levels of co-operation with quite different characteristics.

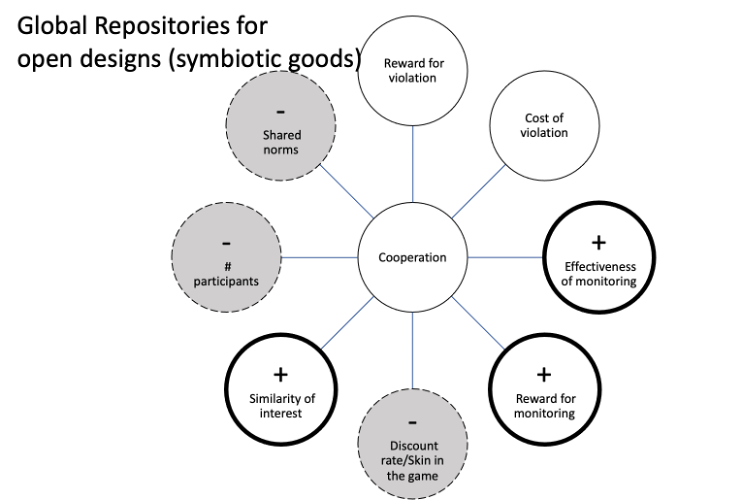

On the global part we have the following:

Global communities do not necessarily share norms. There is wide variety between cultures and nations.

There isn’t much of a reward for violations as results are anyway freely or at low cost available.

Cost for violation is not necessarily big especially if one can work through pseudo-anonymity (but there are ways to mitigate this)

Effectiveness of monitoring is high as everything on the blockchain is public.

Reward for monitoring can be made to be good

If people can work behind pseudonym, they do not necessarily have much of a skin in the game, especially as it can be assumed there are several competing repositories for the same categories of goods

Similarity of interest should be high on a repository of given type of assets

Number of participants is high.

This indicates that there needs to be quite a lot of effort put into designing and simulating the right incentive structures, to get the token engineering right.

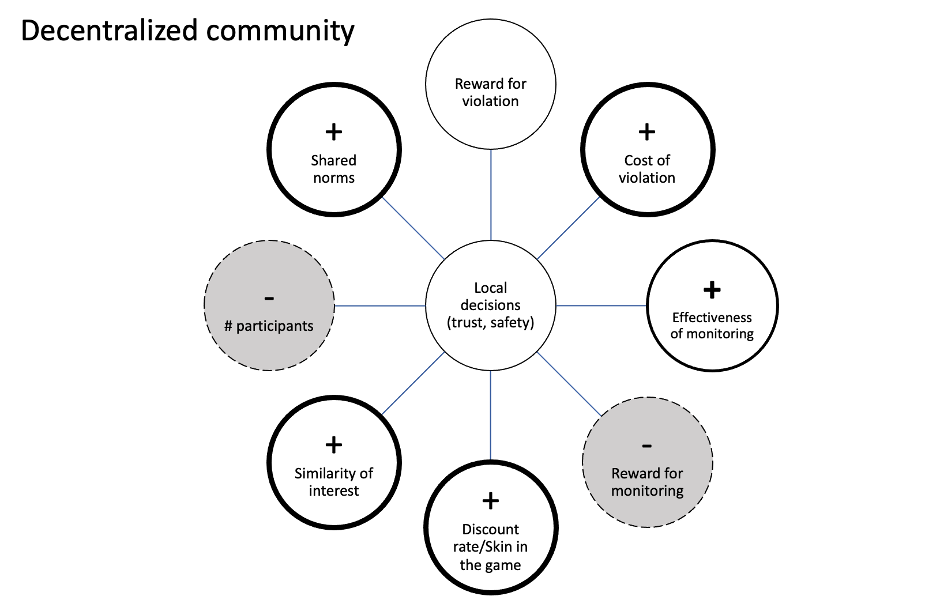

Local communities have much more cohesion, making the environment for co-operation more favourable:

Local communities tend to have share norms.

There isn’t much of a reward as results are anyway freely available.

Cost for can be high as people often are in day-to-day interactions and maintaining good reputation is important

Effectiveness of monitoring is high as everything in on the blockchain and people who live nearby necessarily come to know one or two things about each other

Reward for monitoring often is mostly reputational

As people live nearby for longer periods of time, they do have common interest for local prosperity and skin-in-the-game

Similarity of interest should be high on a repository of given type of assets

Number of participants ranges from small to somewhat large so effect varies but tends not to be too dominant.

Next: Solving Complex Problems