Legalising Property

Next: Miethäuser Model in Education

In previous posts we looked at the power of property laws and what practical problems outdated legal frameworks cause for people and how they clamp down whole societies.

There are a few ways to get out of the conundrum:

Either governmental focus and programs to clear the dead woodwork from the legal frameworks

Miethäuser model described in this post

Legalising Extralegal Property

How to change extralegal property into regular property and unlock its potential?

There is always the possibility that governments get interested and organise a comprehensive program of removing bottlenecks. These programs would always be specific to each country and its legal intricacies.

A more general model is a modification of the Miethäuser Syndikat concept used for self-organised house projects in Vienna.

The central problem in extralegal settlements is as follows:

In emerging markets, a lot of people live in informal settlements on land where they do not have property rights or live in old derelict blocks of flats. They would like to continue living autonomously without the fear of eviction and develop the area on their own terms. However, there is always the possibility of the land being possessed for new developments and them getting legal eviction orders.

Investments into legally acquiring the property are beyond their personal means. Bank loans are either not available because they do not have steady income or too costly to obtain due to interest and amortization sums being more than they can afford. For such projects to be financed successfully, the interest rates of the loans need to be very low. Another option is direct loans from people who consider the cause worthy of their support.

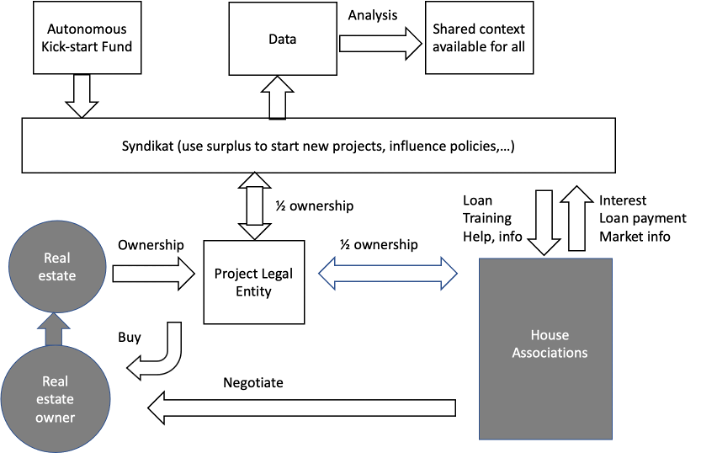

Let’s create an umbrella organisation covering a fleet of such cases and call it the Syndikat (word used in the Vienna approach). The first step is to collect the initial capital sum for the Syndikat. This can be either done via donations or by starting an autonomous fund that operates according to the Inexhaustible Treasures model (collecting interest on interest until there is enough described in post on Schrödinger’s Fund).

Once there are enough resources, the Syndikat kicks into action.

The Syndikat loans initial funding to already existing community(ies) that are trying to legalise their position. These funds are for them to proceed through the legal fluff (hire lawyers, launch campaigns to raise awareness and change laws). Later as experiences gather, it starts acting more as a background support organisation distributing advice, best practice and forming a common big-picture for all self-empowered communities.

In other words, it’s a kickstarter for self-organizing communities to legalise their property.

In more detail it goes as follows:

There is a lot of knowledge needed to navigate the treacherous waters of legal practice. New projects need to learn how to create the right legal form for their association, how to conduct sales negotiations, how to navigate the political landscape and also very importantly how the dynamics work when founding formal associations. This part could start as expert advertise and later some parts or all be digitalised and automatised in similar manner as described in the F1 support model.

On top there is knowledge needed for any needed renovation and construction work for example if the building where they live is extremely run down.

The Miethäuser Fund starts by initially loaning money to an association to cover costs during the formative years of the approach. Existing associations are best as they represent people who have joint interests and vision.

The fund is used to pay for a few associations their journey through the system. Once one of these initiatives is successful, we know that there is at least one path through the red tape.

If you consider that there are a lot of folks in similar situation, you can start viewing this from a fleet perspective. All projects hit the same difficulties in the startup. But now we’ve found through trial and error a successfully set of steps in the world of politics and regulation and succeeded.

Already established projects are in a position to give advice to starting new initiatives – mentoring or online learning courses can be developed in local language to scale up the approach.

Successful projects start by paying back the loan and supporting starting projects or projects in distress via mentoring. The interest for the initial Syndikat loan is zero or very low so this should not be a too big strain on succeeded projects and they should be in a position to increase their earnings by investing into whatever is their business.

Part of the back payment is transferred to starting projects. Established projects can also participate into public debates in political disputes over contested real estate and influence the local legal frameworks and public discourse in general.

This co-operation between autonomous projects does not happen on its own but needs someone to organise it – some superstructure to oversee the transfer of money, information and political influence and communications.

There is risk that projects with now good economic standing after having benefitted from initial support and zero/low interest rate and having paid it back decide to unilaterally exit the system and stop paying solidarity transfer. Then they can proceed to sell their property for a very good profit.

To prevent this in the Syndikat model the property is owned by a shared legal entity where the Syndikat owns half having one vote and the association owns the other half having one vote. Neither side cannot unilaterally change the rules as the ownership is bound together. This prevents taking advantage of the model without reciprocity.

More on the model used in Vienna for their use case: https://www.syndikat.org/en/

The Miethäuser model cannot be directly applied to extralegal property, however. It is excellent when the legal owner for the property is purchased from its current owner (the Vienna model) but in the emerging markets the people already own the property. They have bought it but just don’t have the formal title.

A variant that mght work is that payback and some contribution to the Syndikat, the double ownership structure is dismantled and full ownership reverts to the owners.

As mentioned, the Syndikat can also be a DAO that has no permanent staff but hires various expert in different phases – say as project managers or to validate loan applications. It could work also a peer-to-per lending service. This is however an environment where a lot of experimentation seems likely in finding right path and right legal structures that differ from country to country.

A plus side for a DAO would be that it allows giving participating communities governance tokens for prompt payments and for mentoring other communities. This gives incentive to continue being part of the concept.

Governance tokens allow participating communities to vote and steer the direction of the DAO in future. Communities may also sell them to get money (if DAO is so set up). In latter case the DAO treasury buys these tokens and “burns” them, thus giving them a value.

Communities can consider becoming DAO investors themselves. They have the know-how of how to succeed and have connections to nearby communities in similar situation. As peer lenders they are best positioned to lend to the right entities and with their own work can secure back-payments and interest. In this option the participating communities start earning by helping other communities legalise their extralegal property.

Of course, there are alternatives to this model. In Singapore government-built housing for less affluent is common. In Finland after the second world war when 11% of the population had lost their homes, the government just gave public land to these internal refugees. They were mostly farmers so they could build a new home and start farming on a new lot of land. There was even a free design drawing for building your own house. This prevented any potential social unrest. (For those really interested, there was a coercive law for purchase of land with a principle that land was bought mostly from farms in state of decay or where the primary income was not agriculture. This resulted the farms being rather small and not in optimal places that later affected the agricultural sector to some degree as we had lots of small farms being not so profitable).